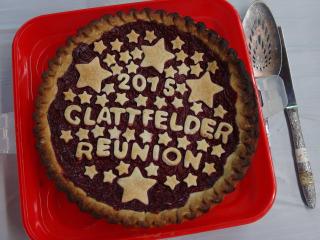

Our 110th Reunion

July 25th and 26th, 2015

Reunion Theme: The Glattfelders in World War II

Fellow members of the Glattfelder family,

The 110th annual family reunion “Glattfelders in World War II” was held at Heimwald Park on Saturday, July 25 and Sunday, July 26, 2015. There were over 200 in attendance on Saturday, and over 130 in attendance on Sunday.

Following our long-standing tradition, awards were given out to the following:

The Oldest Attendee: Pauline Garner (96 years of age)

The Youngest Attendee: Harper Grace Smith

The Person Coming the Greatest Distance: John Garner (Tacoma, WA)

The Registrar’s Choice: WW II Veteran Lavern Gladfelter

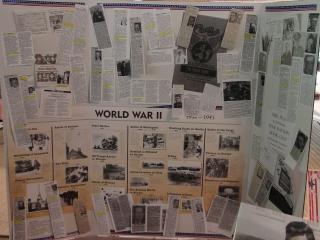

Glattfelders in World War II

The Glattfelders in wars theme continued at the 2015 reunion with World War II. Lila Fourhman-Shaull, from the York County Heritage Trust and a Glattfelder descendant, and Historical Committeemembers Jean Robinson and Philip Glatfelter spoke on the war:

Lila provided a transition from World War I to World War II in York County:

“This is the war to end all wars,” as President Woodrow Wilson described the Great War that ended on the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. Unfortunately, we know how that worked out.

The Roaring Twenties was a time of social and political change that saw more Americans living in cities than on farms. In York County, there was a steady growth in population that combined with an increased dependence on technology. York County had 632 factories during the 1920s that manufactured more than 100 different products. Agriculture was declining as reflected by the over 8,400 farms tallied in 1920 to just over 7,900 by 1935.

National events during the 1920s and 1930s affected York County, including the 18th Amendment that prohibited the manufacture of liquor and the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote. York countians saw the opening of the Lincoln Highway garage in 1921, heard Lancaster’s WGAL on their newly-bought radios and went to the Valencia Ballroom.

Black Thursday, October 24, 1929, saw the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. York County’s agricultural and industrial diversity initially helped residents weather its impact locally. The York Hospital opened its new facility on South George Street in 1930. But the Depression deepened as seen by the closure of many of the county banks, such as in Dover, Jefferson, Glen Rock and Seven Valleys.

By 1932, national unemployment reached 24 percent and in York County it surpassed that, reaching 37 percent as reported by the York Dispatch.

Though not a time of war, a Glattfelder serving in the military was a casualty at the time. Richard Glatfelter died in an automobile accident in October 1933. Richard, who entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1929, was returning to Camp Dix, N.J., after a brief visit with his parents, David L. and Anna L. Glatfelter in Columbia, which is just across the Susquehanna River in Lancaster County.

Richard became a second lieutenant of Infantry after graduating from West Point and reported for duty with the 18th Infantry at Fort Wadsworth, N.Y., before serving with Company H of that regiment at Fort Dix.

On Armistice Day 1937, a new athletic field for Columbia High School was dedicated in Richard's name, with the property donated by his father.

Richard was the uncle of longtime Casper Glattfelder Association board member Philip H. Glatfelter of Columbia. Philip is the only Glatfelter remaining as a trustee with the organization that oversees the field and its activities.

The last trolley ran in York in 1939 and world tensions were increasing with Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Following the day that would live in infamy and the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many York Countians volunteered for military service. As men left the work force, women filled their shoes.

Following an example set during WWI, S. Forry Laucks refitted his company, York Safe and Lock Company, for armament production. Other York County companies came forward, and the Manufacturers Association appointed a defense committee to organize and coordinate wartime production.

The Bits and Pieces Committee created a subcontracting program that linked the prime contractors with subcontractors and also acted as a liaison between government contractors and local businessmen. The York Plan, as it became known, was to organize workers, machinery and materials to achieve high productivity for the Allied Cause. Fifteen points detailed the plan with the motto, “To do what we can with what we have.” Following the plan’s unveiling in New York City, federal officials came to York to meet with the key business leaders.

Many York County companies became defense contractors and their workforce produced much-needed products for the war effort. Of the over 260 Glatfelters listed in the 1943 York City Directory, at least a third of them were so employed.

An example of a company’s participation in the York Plan was the P.H. Glatfelter Paper Company, a producer of fine paper products prior to the war. It would become a subcontractor of winch parts for McGann Manufacturing as well as ordnance parts for York Safe and Lock.

Jean then continued the program.

As York County transitions to an economy of war production after a harsh depression, there are rations on metals, rubber, tires, gas and food. Victory gardens become popular and there are ration cards everywhere. There are tin can collections, drives for food at churches and buddy bags containing toilet articles, playing cards, reading and writing materials, YMCA and USO gatherings, and, lest we forget, “Rosie the Riveter.”

After a “war to end all wars,” we found ourselves yet again receiving the call to service for our family and friends. Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor, “a date that will live in infamy,” will define the years ahead.

Again, Glattfelder men and women respond to the call. These were men and women who lived in towns and villages all over York County and areas beyond. Farmers and laborers, professionals called to action. Some served stateside while many were shipped overseas. We honor all of them today for their duty, wherever their assignments.

What about our Glattfelder men and women who served? There are a few lists available, and one I compiled from obituaries found in the family file at the York County Heritage Trust. Many of the obituaries contained military service information and some photos of the service men included on the display board.

The information collected was varied and interesting and surprising. Several letters received from our request in our newsletters asking for any service related to our Glattfelder family members were greatly appreciated.

Freman Glatfelter was employed in a Red Lion cabinet company before entering the Army in 1941. The Army sent Freman to officers candidate school and he graduated with a new rank of 2nd Lieutenant. He was assigned teaching duty at various posts, and in 1943 found himself in Europe with the 343rd Infantry.

His widow, Janet, has graciously offered his uniform for display here today. And I believe a special photo of her granddaughter visiting Glattfelden rests easy in his pocket.

Harry A. Gladfelter, son of Harry Foster and Ethel Gladfelter, served in the Navy as Petty Officer Second Class. Harry was a boilermaker by trade, so he was assigned duty to repair crippled ships headed to Europe.

Leaving stateside, he was sent to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where he worked in the U.S. Navy shipyard. In conjunction with his mechanical ability, he would “go to sea” to find ships in distress, help bring them back to port and re-fit the ship to go back to sea duty.

The Germans patrolled the Atlantic Ocean and they came in contact with a ship Harry and the crew were towing into port. This ship was full of munitions and when the Germans torpedoed it, it created such an explosion that it turned night into day.

This information is from an account that Harry’s son sent to us about his father. It clearly illustrates dangers in areas of support, not necessarily on the battlefield.

Blue Star families were families that had a son or daughter serving in the military overseas -- one blue star for each individual. Gold Star mothers were the family that lost a soldier in service overseas. These stars would hang in the windows of their homes.

Nelson Glatfelter sent a letter to us which included a copy of a newspaper clipping headline mentioning a four-star family. The headline reads: “WAC Home after 4 Years - third in 4-Star family.”

The WAC soldier was Gladys V. Glatfelter, daughter of Frank and Cora Glatfelter. Having entered the Army in 1942, she received her training stateside and went overseas to England and France.

Her brothers also were in the military: Noah, Navy SeaBees; Robert, Army; and Richard L., Navy. Richard would later serve on the CGAA Board of Directors, from 1985-2000.

Other women with Glattfelder ties served in the Nursing Corps.

Pauline Montoro, daughter of Harry C. and Clara Gladfelter Ginter, after graduating from William Penn High School and York Hospital School of Nursing, joined the Nursing Corps. However, I don’t know where her duty station might have been.

Pattie L. Levis, daughter of George A. and Annette Glatfelter Goodling, entered the Army with the rank of 1st Lieutenant. Her duty calls were Normandy, Northern France and the Rhineland. She received a European African Middle Eastern Theater Campaign ribbon with three bronze stars, National Defense Medal, Victory Medal and French Jubilee Liberty Medal. I might add that she had two brothers in the service, Robert and Richard, both members of the U. S. Army.

I found the name of Dorcas Gladfelter, daughter of Auburn and Lenore Gladfelter, who served in the U.S. Navy, but I don’t have a note of her duty station, as well as Elizabeth P. Gladfelter, who served in the Women’s Army Corps in 1943.

One large Glattfelder family had several sons who served in the armed forces. I don’t know if they had the Blue Stars in their window, but surely would have been eligible.

This family here in York County was John H. and Lizzie Bailey Glatfelter. Their sons: Millard L. Glatfelter, Army, serving in the African and Italian theaters with the 630th Coast Artillery Anti-Air Craft; Walter R., Army, who served in the Pacific Theater of Operations; Allen R., Army veteran, who received the Jubilee of Liberty Medal from the French government for his participation in the D-Day Invasion; Roy L., Navy veteran, who served as a Seaman 1st Class in Guam; Victor, U.S. Army, 108th Headquarters Battalion, 1945.

I believe John and Lizzie’s family consisted of a total of 17 children and there may have been other sons in the service. I will also note here that on our Memorial Page of today’s program that their sister, Frances Rohrbaugh, died April 17 of this year and was the last of her brothers and sisters from this family.

York County Glattfelders were called to serve in many capacities in their respective military service.

Harry T. Glatfelter was a tool and die maker for A.B. Farquhar Co. However, he acquired employment with the U.S. Naval Ordnance in Washington, D.C., where he worked on the Manhattan Project (a secret project prior to the bombing of Hiroshima). He received a citation for his achievement. More than likely, he was a system analyst.

His brother, Arch P., served with the 395th Service Squadron in the Army Air Corps. Later, in civilian life, he received the European Theater of Operations Medal, W2 Victory Medal and American Campaign Medal. After the war, he continued his life work as a draftsman with Bowen McLaughlin York.

The two brothers were sons of Penrose and Lizzie Thoman Gladfelter.

A personal insight from Paul Glatfelter, who served with the 91st Chemical Motor Battalion attached to the 3rd Army Division, in an interview by the York Sunday News:

“Gen. George Patton was referred to as ‘Old Blood and Guts‘,” Paul commented. “It was our blood and his guts.”

Paul was part of the Central Europe Rhineland (sometimes referred to as the Bloody Bucket) and the Bulge.

“I wasn’t paying much attention to where I was. … I was looking forward to getting back on the boat and getting sick again, like I did on the way over.”

He remembers, “we would dig fox holes to keep warm as it was (bitter cold) and were lucky to wash our faces now and then. It was just miserable. There was a lot of frostbite and I was scared most of the time. … Most of the time everybody was.”

Patricia Gladfelter Graham’s husband, Carl, fought with the 28th Army Division, one of the most decorated divisions, also known as the Keystone Soldiers. Many from Pennsylvania were made up of mostly National Guard units. Carl made his way into France a few days after D-Day on June 12. The 28th insignia is on his headstone, “The Bloody Bucket.” Carl and Patricia, the daughter of Eli and Angeline Gladfelter, lived in Ohio. Carl died in 1995.

And three sons of Jacob and Cora Luckenbaugh of North Codorus Twp. served our country:

Charles A., U.S. Army; Reuben E., U.S. Army; and Jacob H., U.S. Army, who served in the military police in Company C 797th MP Battalion. All three returned home to lead quiet lives in their communities.

When I received Joanne Martin’s letter, I knew she had a Glattfelder connection since I had met her here several times over the years. Her brothers were veterans of World War II: Lieutenant William H. Martin, U.S. Navy, the Italian campaign and North Africa; and Sergeant Paul R. Martin, U.S. Marines, the South Pacific and Iwo Jima. Their parents were Frank and Helen Gladfelter Martin.

Helen’s nephew, Pfc Kenneth Gladfelter, son of her brother Henry, served in the Army infantry as a paratrooper and lost his life over Holland. His marker is in Margraten, Netherlands, cemetery, dated 29 March 1945.

Phil will relate two other stories of interest about Glattfelder relatives serving in the South Pacific Theater of Operation: Art Glatfelter and Barney Oldfield.

Phil then gave accounts of Art and Barney:

A boy and his dog.

Many a boy could talk about the wonderful times spent with their dogs -- their friend; their pal.

Arthur J. Glatfelter Jr., who was a Casper Glattfelder Association board member for 34 years, was one such boy. But the time spent with his dog, Pal, went far beyond the confines of their York County home.

Their relationship grew even closer as the 15-year-old Art turned to Pal, a German shepherd he got as a puppy when he was 14, for comfort when Art’s father and brother died in a boating accident. Pal would sleep next to Art while he did homework and at the foot of Art’s bed at night. Weekends, Art and Pal spent hunting, fishing or exploring, and thinking about the war.

A year later when he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, Art left behind his mother and his beloved dog. But when Art came home on a holiday pass, he took Pal with him to Camp LeJeune, N.C.

Dogs were not permitted at the camp, but Art’s quarters were in a secluded section and it was easier to hide Pal. After an initial protest, the mess sergeant, who bunked next to Art, soon became one of Pal’s friends. Consequently, Pal sometimes ate better than the Marines. “Everyone from a major on down really loved him,“ Art said in a York Daily Record article in 2006.

Art would soon depart for the Pacific, and he decided to enroll Pal in the service. The dog ended up going through training to become a hardened tracker of the enemy. Pal had a new master, named Ben, and Art’s chances to visit his boyhood friend became more and more limited. “Just take good care of my dog,” Art told Ben. “Don’t worry. We’re going to be real partners,” said Ben.

Art was sent halfway around the world from Camp LeJeune, to Guadalcanal. Pal was a perfect candidate to join the service, and soon was trained and became part of the 3rd Marine War Dog Platoon. The dogs were taught to smell and locate nonmetallic mines, as well as enemy soldiers hiding in the jungle.

The day Art’s ship landed in Guadalcanal, another ship left North Carolina, with Pal aboard. “This is it, fella,” Ben said to Pal, according to a story about Pal written by Robin Atwood Fidler. “We’ll see how well we’ve learned our lessons.”

One day, news reached Art that a group of trained dogs was on the other side of the island. He had no idea where Pal had been sent, but he couldn’t resist the temptation to try to see his beloved Pal before they both entered combat in the jungles of the Pacific - Pal to seek out enemy soldiers and Art to fight them. Besides, there wasn’t much to do in the days before they shipped out and nobody wanted to sit and think about what lied ahead.

When Art and a buddy arrived at the dog enclosure, Art immediately spotted Pal. Ben was glad to see a familiar face, but admonished Art. “You’re not supposed to be here,” said Ben, according to the Robin Atwood Fidler story “Pal’s not to have anything to do with you.”

Despite the trainer’s orders, Art reached out to pet his boyhood friend. A wag of the tail told Art they were still pals. And it meant home and family and life before the war. “You do know me, boy,” said Art. “I knew you could never forget.”

But there was still a war to wage, and Art was led away so that Pal would remain the hardened scout dog, not the pet.

Pal went on to lead Marines on 40 combat patrols in the jungles of Guam. Not once did he fail his duty, frequently alerting the Marines to enemy forces on the trail ahead.

About a year later, Art received a letter from his mother that included unexpected news about Pal. He had been promoted to Corporal. Art now knew that Pal was alive and he was a success. Art was proud to be a Marine, and at least equally as proud that his dog was serving his country.

In 1946, Art and Pal were honorably discharged as sergeants of equal rank. The two shared a barracks again at Camp LeJeune, but Pal was discovered and ordered off the base. Art sent Pal with a friend who lived in North Carolina.

When Art was discharged, he realized that bringing Pal back to York would be a mistake, and did what was best for the dog, leaving him in North Carolina. “I checked on him from time to time,” Art said in a 1995 York Sunday News article, “and from what I could find out, he lived a good life in the mountains after the war.”

Pal lived into the early 1950s and is buried in North Carolina.

The story could end there, but more should be added. In 2006, -- more than 60 years after Art and Pal served -- a statue was unveiled during a Veterans Day program at the York Expo Center. Nearly 1,100 local U.S. veterans were in attendance. Art, always unflappable, was stunned when he saw the statue of his dog Pal, which was erected to honor Art and Pal for their service, as well as Art‘s many contributions to the community.

Art went on to found the Glatfelter Insurance Co. and was a pillar of the York community. He served on the Casper Glattfelder Association board of directors from 1979 until his passing in 2013, and was an integral part of numerous park projects as well as a generous contributor.

Art, son of Arthur and Margaret Glatfelter, is a descendant through Casper’s son John. His daughter Bonnie is currently a CGAA board member and our association’s treasurer.

Another Glattfelder relative with a World War II story to be told is Barney Oldfield. His interesting story will not end with the war though.

Oldfield, who was born Dec. 18, 1909, in Tecumseh, Neb., was actually christened Arthur Oldfield. But he was so enamored with the fame and exploits of his distant cousin and race car driver of the early 20th century that he legally changed his name to Barney Oldfield, according to a story written by his niece, Margery Lee Oldfield.

Barney attended the University of Nebraska, graduating in 1932 with a degree in journalism. He also participated in the ROTC program, through which he was immediately commissioned into the U.S. Army.

During his first summer encampment, Barney initiated the forerunner of the U.S. military’s hometown news release program, writing “hometowners” articles about his fellow infantrymen.

In 1941, Barney became the first newspaperman to complete paratrooper training. During the war, Oldfield served as a press aide to Allied commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was also integrally involved in the D-Day Invasion at Normandy.

Oldfield met Eisenhower when he was stationed in London. He was in charge of setting up press camps to follow the troops across Western Europe, but soon became Ike’s press agent.

In a May 22, 1994, Los Angeles Times article, Oldfield recounts a situation leading up to the D-Day invasion. “The 101st Airborne had a display of weapons,” he said in the article. “(British Prime Minister Winston) Churchill asked Eisenhower how many yards the 81-mm mortar would reach and Eisenhower said 3,000. One of the soldiers piped up and said ‘3,250.’ Eisenhower turned to him and said, ‘Son, you’re not going to make a liar out of me in front of the prime minister for a lousy 250 yards.’”

Later in the story, Oldfield recounted: “Churchill … got up on the hood of a jeep. He took off his bowler hat and out of his mouth came the words I will never forget: ‘I stand before you with no unrealized ambitions except to see Adolf Hitler wiped off the face of the earth.’”

During the Normandy Invasion, Barney was recruited as the only American member of Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s command. He wrote twice-daily communiqués during the invasion and upon entering Berlin in 1945 was responsible for bringing in all of the Allies’ communications equipment.

Upon entering Adolf Hitler’s underground bunker, Oldfield recounted in the story by his niece, he located Hitler’s large marble desk. Feeling the need to make an appropriate gesture at that moment in history, Barney unzipped his pants and “let go” on Hitler’s desk. Both Eisenhower and Churchill complimented him on his actions.

They say behind every great man is a woman. For Barney, it was Vada, his wife of 63 years, who also served in the military. She was one of the original WACs and served 24 months in Africa, Sicily and Italy in communications with the Hq 12th Air Force.

Barney’s media interest and expertise continued after the war. Soon after, he and Vada moved to Beverly Hills, Calif., where he became a well-known publicist for Warner Brothers Studio for two years. He handled PR for stars such as Errol Flynn, Ann Sheridan, Jane Wyman, Ronald Reagan and Elizabeth Taylor.

He then reentered the Army in 1947 before being transferred to the Air Force in 1949. He was asked to reassemble his press corps during the Korean War before being recalled to Washington to help Eisenhower set up the Air Forces of Central Europe. His last military assignment was as Director of Information at NORAD.

Barney retired from the military in 1962, having served 30 years, three months and 25 days, and the Air Force commissioned “The Colonel Barney Oldfield March,” which was recorded during his retirement ceremony.

Barney went on to author several books, including “Never Shot in Anger” in 1956, which was reprinted in 1989 as the “Battle of Normandy Museum Edition,” and his autobiography, entitled, “The Kid from Tecumseh” in 2002.

Barney also appeared in movies, playing himself in “Into the Breach: Saving Private Ryan” in 1998 and “Marlene Dietrich: Her Own Song” in 2001. According to the story by his niece, her father told a story of Barney’s friendship with Dietrich, a German actress and singer. When Dietrich’s mother died during the midst of the war, the Germans wouldn’t allow her to bury her mother. She asked Barney to help, and he and a group of soldiers, “under the cover of darkness,” carried her mother’s corpse into a nearby forest where they held a brief ceremony, then buried her.

Barney was also head of international public relations for California-headquartered Litton Industries for 27 years before his retirement in 1989.

The Oldfields gave more than $3 million to charity and established more than 250 scholarships. Among those are the Nebraska Normandy Scholarships, made possible by a $50,000 endowment by the Oldfields. The scholarships honor four Nebraskans who died during the assault on Omaha Beach.

“June 6, 1944, still haunts Vada and me,” said Oldfield in an April 1994 article in Senior World/Los Angeles. “I’ve visited Normandy many times since and each time I’ve returned, I’ve come away with an even greater sense of wanting to somehow honor all those who participated in the great liberation effort.”

Oldfield also founded the Radio and Television News Directors Foundation. In 1994, the group’s trustees awarded the first Barney Oldfield Distinguished Service Award to the person they felt was the most deserving: Barney Oldfield.

Oldfield met former heavyweight champion George Foreman while Foreman was a young boxer in Los Angeles. Foreman described Vada as a kind of surrogate mother for him and a lifelong friend. Vada passed away in 1999.

Other honors for Barney included a six-mile stretch of highway near Tecumseh named the Col. Barney Oldfield Memorial Highway in 1997; induction into the Nebraska Journalism Hall of Fame the same year as a “living Nebraska journalism legend,” along with historical figures Willa Cather and William Jennings Bryan. CBS correspondent Charles Kuralt once called Barney “The King of Press Agents.”

As a side note, in a small packet of information stapled together in our Glattfelder archives that includes correspondence with the association, a business card from Barney is included. On one side, it says: Important phone numbers: George Bush (with a number I won’t reveal); Ronald Reagan (another number); Elizabeth II; Pope John Paul II; Helmut Kohl; Mikhail Gorbachev. On the reverse side, it says: But If You Really Need Help … The Col. Barney Oldfield Organization Inc., P.O. Box 1855, Beverly Hills, CA 90213, and the phone number.

Oldfield, son of Adam and Anna Oldfield, died in 2003. He is a descendant of Casper through Casper’s son Felix.

Jean then closed out the Glattfelders in World War II program:

Betty Oberg Hoffman communicated with us that both her brothers put on the uniform: John C. Oberg, U.S. Navy, “rescued survivor of the sinking ship USS Wasp, aircraft carrier in the pacific; George W. Oberg, U.S. Army, served in Europe and the Battle of the Bulge.

The family lived in Nebraska. Their parents were Amy Gladfelter and Ernest Oberg.

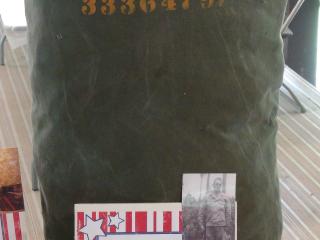

Then Susan Rudnick contacted us and asked if we would like to display an army duffle bag with the name Glotfelty on it. Of course!

However, there was more of a story as the email went on. Seems like Uncle Willard Rafferty, whose mother was one of those Glotfeltys, always told that he was “in intelligence” during the war years.

The story, retold by Willard’s son, Scott, follows:

“Dad served in the European Theater during WWII in the U.S. Army Signal Corps as a very young officer for about four grueling years. For now, just one fun story he told us recently -- last fall -- about an incident which launched the decisive "Battle of the Bulge." Dad was perhaps a lieutenant or captain in his Signal Corps unit when an order came in from General Eisenhower's headquarters: The general wanted an absolutely secure communication line set up for a three-word command to be issued.

Dad's unit commanders, much higher-ranking men than he, were both on leave and not available to act upon this high urgency/priority command. But not to worry (I, his proud son Scott, will add this part -- GOD had the right man still ready to act, our Dad! Willard and our mom, Madeline, were not yet married, so none of we "kids" were yet born).

“Willard had years earlier built a phone system as a youth in his hometown to interconnect his parents and other family members' homes before there was a phone company in Ohiopyle, Pa. For his system, he used what he called "voice-powered" handsets. These, Dad knew because of that childhood project, would offer an unbreakable secure line of communication for Headquarters to use.

“But he had to first devise a system to test the miles of phone cable which he planned to have crews hastily install at the proper moment (by simply stringing it up in trees or whatever they could do). But the cable testing before stringing it up was crucial because many of the cable spools they had in stock were known to be defective when suspended under tension -- so the whole system would fail if one defective cable were employed in it.

“Dad devised a "test tower system" to stress-test the cables, in order to ensure they deployed only the reliable spools of cable. Dad said the higher-ranking out-of-town commanders probably would not have known about the "voice-powered" handsets anyway, so would not have known how to make this special secure landline for General "Ike."

“That line WAS completed on time by Dad's leadership and many in crews who installed the tested cables and phones under his direction. The three-word command had to do with coordinating between General Eisenhower and General Patton the exact moment that Ike wanted their secret and pre-planned Battle of the Bulge to begin. It worked. Germany was weakened and the Allied forces pulled off a stunning victory.”

Susan also had an uncle in World War II, Glenn G. Glotfelty, U.S. Army, 60th Field Artillery Battalion, machine gunner, North Africa and Italian campaigns, Central Europe.

I must also add here that Joanna Jones, a former Casper Glattfelder Association board member died earlier this year. Sue’s aunt would have loved this story. Joann was very instrumental in bringing the Glotfeltys back to York County.

York County Glattfelders were ordinary men and women asked to become extraordinary men and women for our military services. The Greatest Generation name was assigned by Tom Brokaw in his book on World War II survivors’ experiences. I believe we can also assign The Greatest Generation to our sons and brothers and sisters and fathers in those war years; years before and the years to follow. And we thank them for their sacrifice and courage so that we can mark this occasion with honor.

All gave some; some gave all. The ultimate sacrifice from our York County Family:

Edgar W. Gladfelter, Army, 2nd Lieutenant, 175th Infantry, 28th Division. Killed in action July 17, 1944, at Saint Lo, Normandy, France, at age 22; son of Edgar W. Gladfelter Sr., Wellsville.

Clarence F. Glatfelter, Army, Pfc 9th Division, died of injuries received at Saint Lo, Normandy, France, husband of Ruth Frey Glatfelter, son of C. E. Glatfelter, Dallastown.

William L. Glatfelter, Army, Major, Army Air Corps, died in and airplane crash at Horn Lake, Miss., in January 1945, stationed in Indianapolis training support; husband of Irene and son of P.H. Glatfelter, Spring Grove.

Kenneth Gladfelter, son of Henry Gladfelter, died in the Netherlands, 1945.

Philip R. Bowman, Army, died in France January 9, 1945, son of Harry and Claudia Gladfelter Bowman.

With the capture of Berlin by Soviet and Polish troops and the subsequent German unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, the war in Europe ended. The United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945 and Japan surrendered on August 15 of that year bringing to an end one more time of sacrifice for our Glattfelder family.